Pierceton Hobbs is a SWVA musician and recipient of the Greater Bristol Folk Arts & Culture Team’s Central Appalachia Living Traditions (CALT) Tradition Bearer Fellowship in 2022-23. This fellowship provides financial support, professional development, and public presentation opportunities for people working in traditional or folk arts and culture.

Tell us all about your CALT Tradition Bearer project

I was very honored to be rewarded the CALT Tradition Bearer Fellowship Grant to support my work as a teaching and recording artist. I used my funds to acquire necessary equipment to practice my art as well as finish a recording project of original music.

How has the grant impacted your craft and your ability to do this work?

Without this grant, I wouldn’t have been able to complete my album. It has been a work in progress since 2022 because of funding issues. I started with an expansive vision and beautiful friends who own a basement studio. They graciously lent their knowledge and expertise in laying down the bones with me. With help from the CALT Tradition Bearer Fellowship Grant, I have finally completed all production and the project is in post-production with a release date set for August 31!

Who are your biggest inspirations for your artistic and creative work and music making?

This is a loaded question, aha! There are so many beautiful people who have either mentored me in some way or helped me come into my own. Apologies in advance if I miss anybody:

Folks:

Tyler Hughes, Sam Gleaves, Thomas Cassell, Will Cassell, Kenny Miles, Hayden Miles, Linda Jean Stokely, Montana Hobbs, Larah Helayne, Don Rogers, Jesse Wells, Matthew Carter, Don Rogers, Mitchella Phipps, John Haywood, Rich Kirby, Senora May, Corbin Hayslett, Chris Rose, Anna Mullins, Ron Short, W.V. Hill, A.K. Mullins, Jimmy Mullins, Ron Kennedy…

Performers:

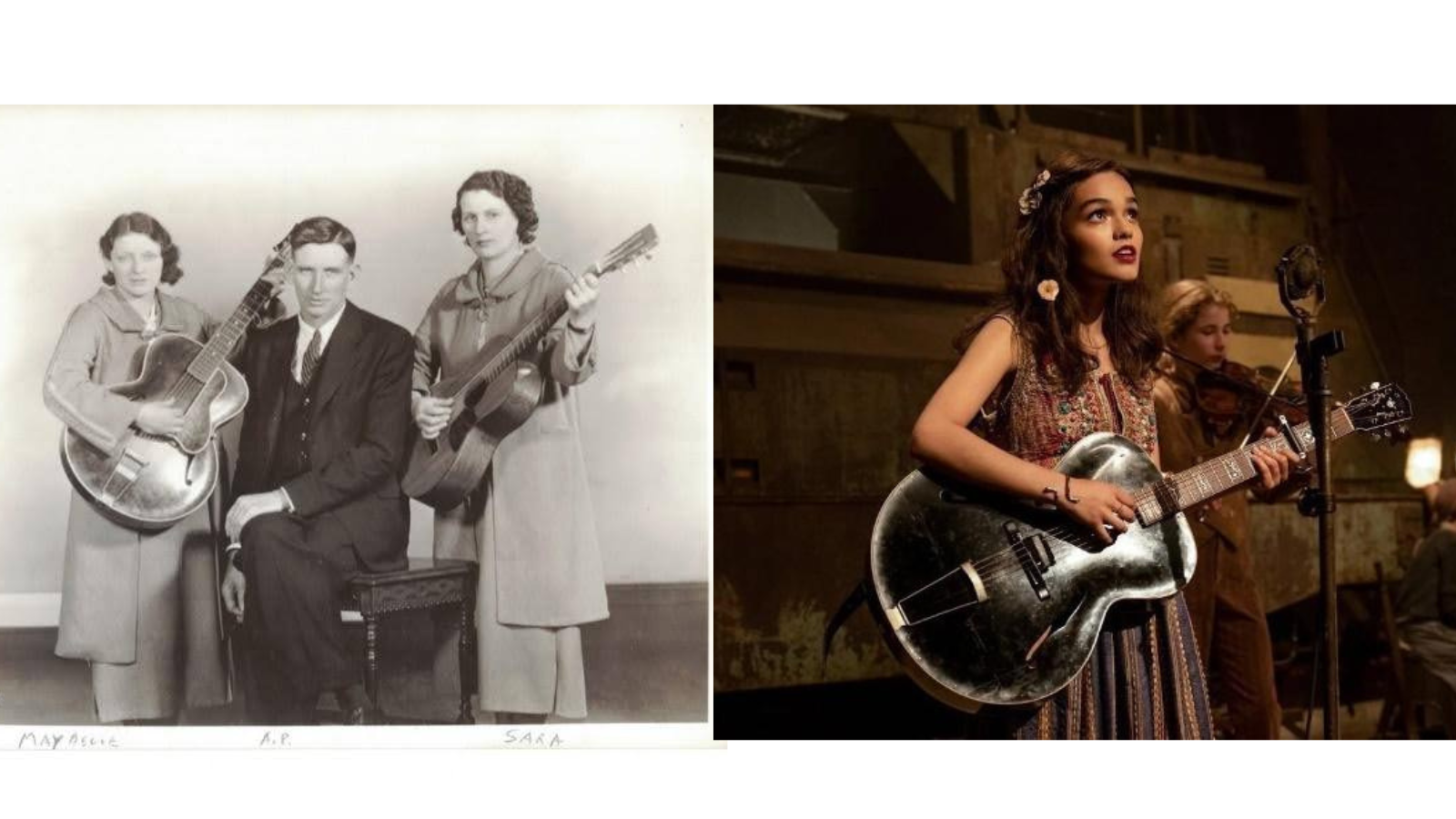

Circus No. 9, Wayne Graham, The Local Honeys, Foddershock, Sparklehorse, 49 Winchester, Geonovah, The Empty Bottle String Band, The Foodstamps, Kaleb N.F.I., Amythyst Kiah, The Stanley Brothers, Jim & Jesse, The Carter Family…

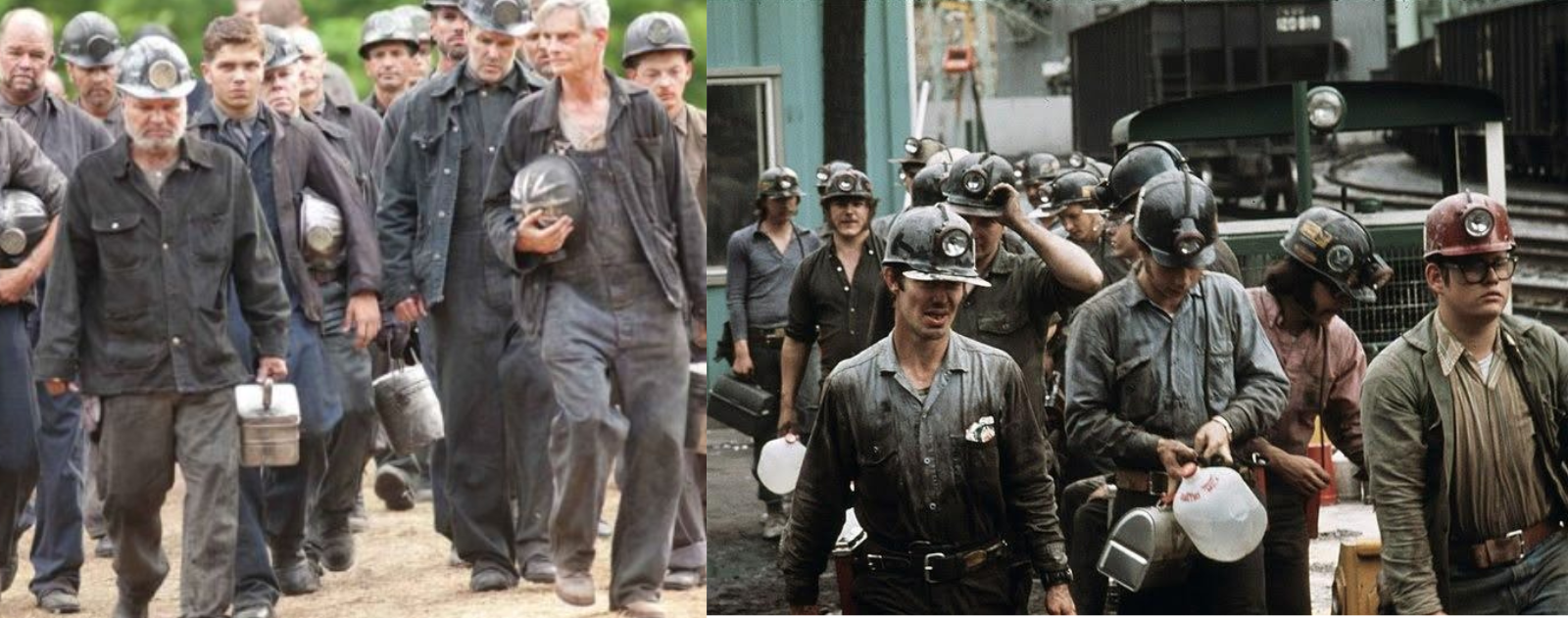

Why do you think your work is important to preserving and sharing Appalachian Folkways?

I consider myself a community-based artist. Every faucet of the work I partake in contributes to capacity building in a resource-deprived area. We have to build the supportive artist community we want to see together!

As a tradition-bearer, I also pass along tunes I have learned (and continue to learn) to students in the local Junior Appalachian Musicians program.

You are an Appalachian artist, a musician, songwriter and storyteller. Tell us what these roles mean to you.

The most astounding thing for me is the tendency of Appalachian artists to stick together like burrs in the wilderness fighting to land somewhere fertile to grow…no matter the genre or level of experience there is support to be had out there.

Songwriting has always proved important in highlighting disparities everywhere, especially here. For me, it’s about comfort. I spill words to get things off my chest, hairy or otherwise. I write and arrange in the context as if I were a spectator or fan looking for something comforting to listen to whether that be happy, mad, melancholy, sad, or silly – it’s all related to human emotion. I try to make music that I want to listen to.

Stories from Appalachia are fluid and ever-changing. I love folktales and carry a few with me but emerging stories are my favorite. I think we’re putting away trauma and collectively lifting each other up…not “by the bootstraps” but with open arms.

Your music tells the honest and true stories of life in Appalachia, be it an original composition or your rendition of a traditional song. What do you want people to take away from hearing these stories and experiences?

I tend to hope listeners have an open mind.

Interpretations of meanings are just as diverse as the experiences we have in life.

You also teach students music, tell us about the rewards of this experience

My students are a blessing! I feel as though they teach me more about the world around me than all of the world’s wisdom combined.

It feels especially rewarding when I show them the basics on any number of instruments and they take flight on their own! When I see that creative spark flare, I think I’ve done what I’m supposed to do.

What is the most difficult thing about being a musician in the Appalachian region? What is the easiest? What do you like most about it?

It’s hard for me to share anything easy about being an artist here. As we talked about earlier, Appalachian artists are very supportive of each other and it’s a beautiful thing. With that being said, there are still so many limiting factors for artists in the region including but not limited to a lack of creative spaces, funding, healthcare, resources, services, transportation, and venues. This subdues our ability to thrive!

Pierceton, is a hotdog a sandwich?

NO! A HOTDOG IS A STAPLE MEAL STEAMING WITH SUSTENANCE AND COMFORTING WARMTH! ESPECIALLY WITH CHILLI!

What projects are you currently working on/ and or what’s next for Pierceton Hobbs You could mention any upcoming craft shows this summer, workshops etc.

2024 is a busy and exciting year for me! This summer, I’ll be assisting teachers instructing traditional music at Cowan Creek Mountain Music School the last week in June. This summer, I’ll be performing and releasing singles in anticipation for an album release on August 31! My first show after the release will be at Bristol Rhythm and Roots Reunion on September 15th!

Folks can keep up with my artistic endeavors by visiting piercetonhobbs.com or on social media (links are accessible on my website).