Today Bristol is celebrating Bristol Train Station Celebration Day, an event highlighting trains and local railroad history through educational programming, arts and crafts, and music.

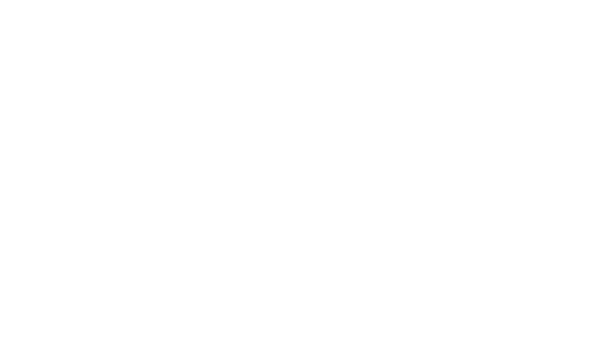

Bristol’s present-day train station was the fourth on its site. It was built in 1902 by John P. Pettyjohn & Company of Lynchburg, Virginia, and the brickwork was laid by John J. Fowler, a local African American master bricklayer. Bristol’s train station primarily dealt with coal and freight traffic, but passenger trains passed regularly through Bristol – and brought Ralph Peer and the Victor engineers to Bristol in 1927, along with some of the musicians who recorded here during the Sessions.

These days, the railroad has lost much of its mystique – visions of crowded commuter trains come to mind – but back when the railroads were first being constructed and rail travel was developing, trains were iconic. And they were especially iconic in music.

Trains and railroads were common subjects in songs during the 19th and early 20th centuries, in a variety of genres from popular music to blues and hillbilly tunes. These songs covered a wide variety of subjects within the train and railroad theme, including railroad construction and specific trains, rail travel and its excitements and dangers, train bandits, the wandering hobo living life on the rails, and even as a spiritual metaphor within sacred and gospel music.

In all likelihood, the first American song about the railroad was a tune composed by Arthur Clifton and copyrighted on July 1, 1828. Known as “The Carrollton March,” it celebrated the ground-breaking ceremony at the construction of the first public railway for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company. This event served as inspiration to another songwriter, Charles Meineke – he copyrighted his song “Rail Road March” two days later and dedicated it to the directors of the same railroad company.

It would be easy to write a piece as long as “The Longest Train I Ever Saw,” and certainly there are whole books on the depictions of railways and trains in song – for instance, Norm Cohen’s Long Steel Rail: The Railroad in American Folksong is a wonderful source. However, this post will touch on a particular type of train song within the hillbilly genre, and one of the most evocative types: songs about train wrecks.

Train wrecks were a common facet of life in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and this was reflected in a lot of songs from the period. While some of these songs lamented passengers who lost their lives, most of them memorialized the crewman killed in the line of duty on the rails. Two of the songs at the 1927 Bristol Sessions chronicled train accidents – “The Wreck of the Virginian,” sung by Blind Alfred Reed, and “The New Market Wreck,” sung by Mr. and Mrs. J. W. Baker. You can read more about the former song here; the latter was based on the 1904 Southern Railway crash of two passenger trains near New Market, Tennessee, where at least 56 people died. Family lore tells us that Sara Dougherty was playing autoharp and singing “Engine 143” when A. P. Carter turned up at her family home selling fruit trees; her singing voice convinced him that she was the woman for him. “Engine 143,” also known as “The Wreck on the C & O,” tells the story of engineer George Alley who was badly injured when his train hit a rock slide on the tracks, later dying from his wounds. This was a particularly popular folk song with over 70 different versions known; the Carter Family version recorded for Victor sold over 90,000 copies and was the most influential, and later artists like Johnny Cash and Joan Baez also put their own stamp on the song.

A train wreck ballad written by preacher Blind Andy Jenkins fell into the more unusual category of songs that focused on the passengers rather than the crew. His song records the collision between two Southern Railway trains – the song’s namesake and the Ponce de Leon – in December 1926. Attributed to an error amongst the crew of the Ponce de Leon, the crash resulted in 19 dead and 123 injured, most from the train that caused the accident. Within two months of the wreck, Jenkins had composed “The Wreck of the Royal Palm,” and it was recorded by popular musician-turned-hillbilly singer Vernon Dalhart for Columbia in January 1927 – this quick release reflects the common practice of rapid production and distribution of “current event” songs on hillbilly records during this time period. Dalhart’s version of the song sold around 36,000 copies. Jenkins also wrote the train wreck song “Ben Dewberry’s Final Run,” which was recorded by Jimmie Rodgers in November 1927.

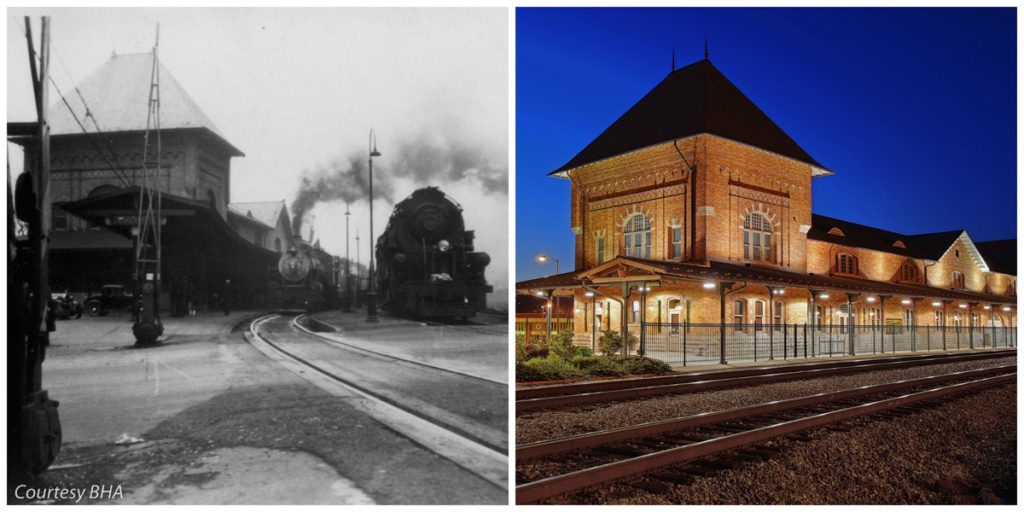

A version of “The Little Red Caboose Behind the Train” by Bob Miller, copyrighted in 1928 and recorded by him in 1930, is a train wreck song that is probably not based in a real happening. Instead, it uses the train wreck as a vehicle to tell a sad and sentimental story – that of a conductor, now old and grey, whose new bride was killed in a wreck on their honeymoon as she rode in the little red caboose behind the train. The song’s last verse delivers home the tragedy of the tale:

“They placed her in the graveyard beside the railroad track,

He still works in the sunshine and the rain;

And the angels all are sober as he rides all alone,

In that little red caboose behind the train.”

Another version of this song copyrighted by John Lair in 1935, however, tells a different story, this time about the loss of the brakeman as the train’s crew tried to prevent a wreck; its details imply that this musical account might be based on a real event.

source: theopendoorway.co.uk (2017), https://goo.gl/jtmvWI

One of the most famous wreck songs is “The Wreck of the Old 97.” The Old 97 was a mail express train that flew off the tracks at a railway trestle near Danville, Virginia, in September 1903, crashing in the ravine below – the engineer Joseph A. Broady had pushed the train to a faster-than-normal speed to make up lost time and then wasn’t able to use his air brakes as the train approached the trestle. The wreck inspired several ballads, one of which was first recorded by Henry Whitter with G. B. Grayson for OKeh Records in December 1923. It was later recorded by Dalhart and released by Victor Talking Machine Company in October 1924 (after he first recorded the song for Edison earlier that year). The Victor version has been heralded as the first million-selling country record in the United States.

However, the tragedy of Old 97’s crash is not the only drama associated with the song. It was also part of a major battle over copyright. The song was first credited to spectator Fred Jackson Lewey (his cousin was killed on the train) and Charles W. Noell, but it was later claimed by David Graves George, who sued Victor saying he was the original writer of the ballad. The case was tied up in court for several years, with the decision favoring both sides at different times; George died before ever collecting the $65,000 in damages he was awarded.

René Rodgers is the Curator of Exhibits & Publications at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum.