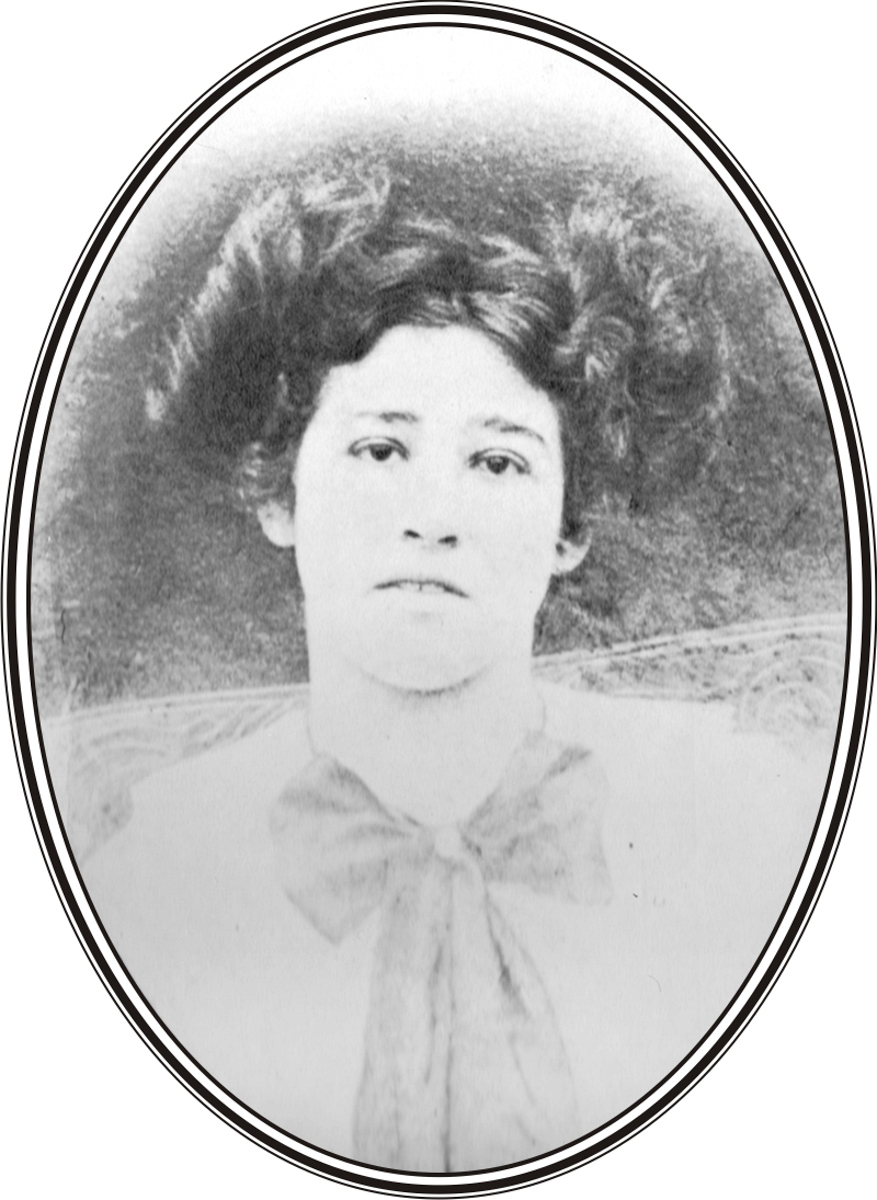

Just 30 minutes south of Big Stone Gap, Virginia, where our bookstore Tales of the Lonesome Pine is located, you will find Hiltons, Virginia, and the Carter Family Fold, home of the famous musical family that started with A.P., Sara, and Maybelle, and included Maybelle’s daughter June Carter. June went on to marry Johnny Cash, whose ancestors immigrated to America from the village of Strathmiglo in Scotland. Just down the road an hour or so is Bristol, Tennessee-Virginia, known as the “birthplace of country music” due to its place in early commercial country music history. A wee bit north is the hometown of Ralph Stanley, who among other accomplishments famously sang “Oh Death” in the movie O Brother Where Art Thou. Just to the west in Kentucky is where the wonderful ballad singer Jean Ritchie grew up.

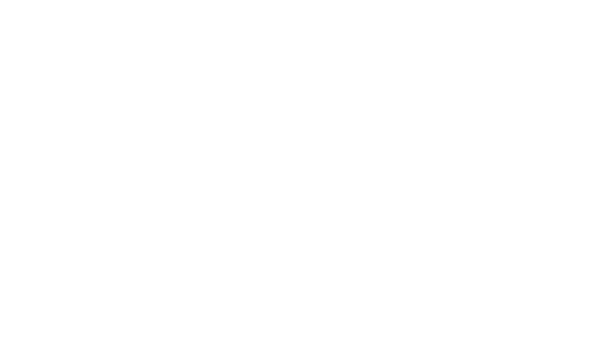

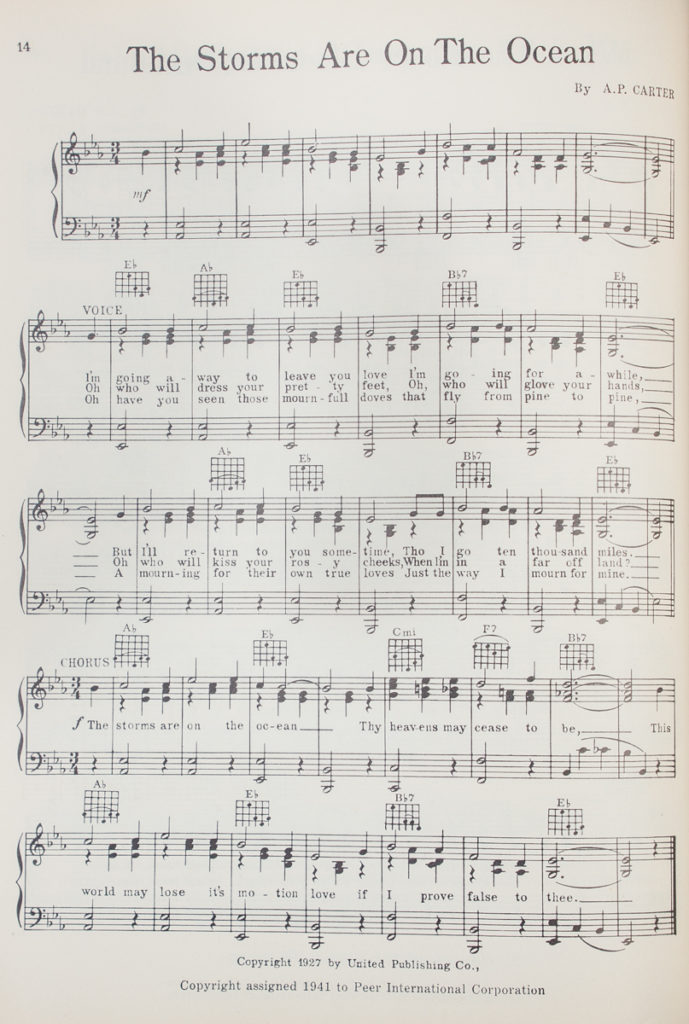

As you can see, it’s an area rich in musical heritage – and one that can be connected to the Old World through song. For instance, one of the most fascinating musical links between Scotland and Appalachia is through the Scottish ballad “Lord Gregory” and its American versions. No less than 30 of the 82 variants listed in the Roud Folk Song Index records are from our adopted state of Virginia. Chief among these is a song recorded by The Carter Family back in 1927 in Bristol, Tennessee, called “The Storms Are on the Ocean”– despite the fact that this part of Appalachia is a few hundred miles inland.

Here are the opening lyrics of “The Storms Are on the Ocean”:

I’m going away to leave you dear,

I’m going away for a while,

But I’ll return to you my dear,

Though I go 10,000 miles.Who’s gonna shoe my pretty little foot,

And who’s gonna glove my hand,

And who’s gonna kiss my red rosy cheek,

Till you return again.

The “Storms” version was long established in the family tradition of the Carters, who also claim ancestry from the British Isles, and the first verse, with its reference to 10,000 miles, might also call to mind Robert Burns’ poem “A Red, Red Rose” Different renditions of the second verse can also be found in many of the earlier versions of this song across the years.

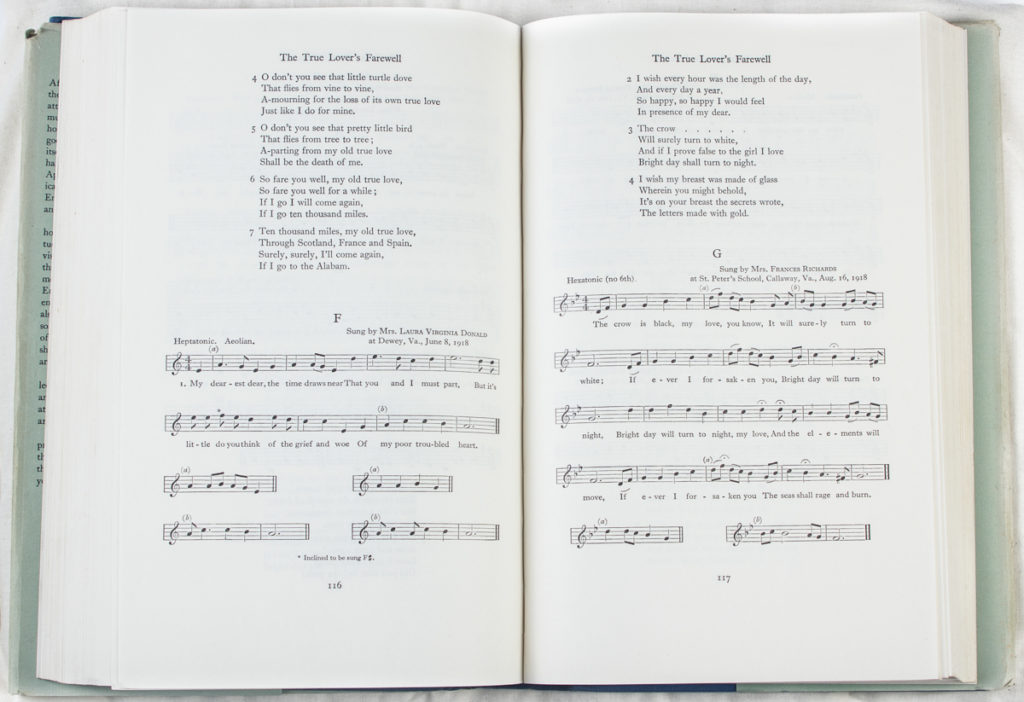

The ballad “Lord Gregory,” also known as “The Lass of Loch Royal,” is listed as number 76 in Francis James Child’s famous collection, English and Scottish Popular Ballads. Child also details a number of mainly Scottish variants. In one the lady sails with her baby from Capoquin to her beloved’s castle, only to be told by his duplicitous mother that he’s away. Sailing back to her home, she is drowned, but not before lamenting over who will shoe her foot, glove her hand, etc.

When Bertrand Harris Bronson produced his collection The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads, he included several “Lord Gregory” variants more reminiscent of “The Storms are on the Ocean.” Like most American descendants of Scottish ballads, the story got stripped down to become shorter and simpler, while the tunes were jollied up in tempo and rhythm.

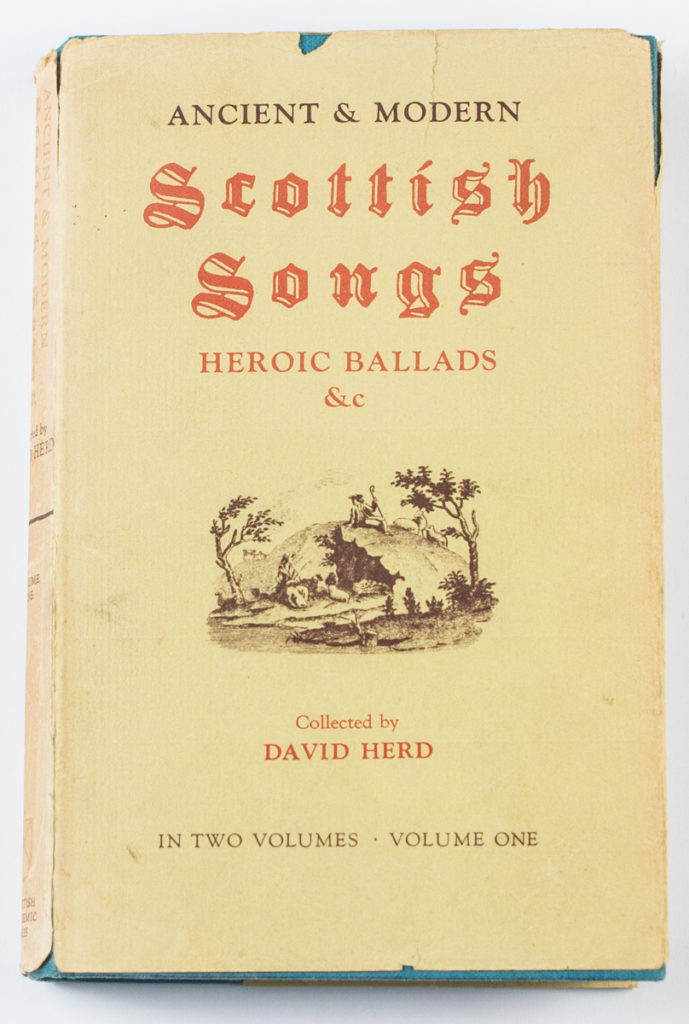

We were delighted to be able to lend a number of books to the Birthplace of Country Music Museum for their new special exhibit The Appalachian Photographs of Cecil Sharp, 1916 to 1918, focused on the ballad collecting done in Appalachia by Englishman Cecil Sharp at the beginning of the 20th century. The books trace the journey of “Lord Gregory” (under various titles) from Scotsman David Herd’s Ancient and Modern Scottish Songs, Heroic Ballads, &c from the late 1700s to Bronson’s record of the tunes from the 1950s, along with the afore-mentioned and famous Child’s English and Scottish Popular Ballads, Sharp’s English Folk-Songs from the Southern Appalachians, and a book about the Greig-Duncan Folk Song Collection from Aberdeenshire in Scotland. We hope you’ll check out the exhibit to explore the journey of the “Lord Gregory” variants across these different books!

The recording of “Lord Gregory” by Maddy Prior on the Silly Sisters album is magnificent, based on an earlier recording by Ewan MacColl. As for “The Storms are on the Ocean,” while many singers have followed in their footsteps, nothing compares to the original by The Carter Family. You can hear both these versions below:

Nor does anything surpass a visit to the Carter Family Fold, a favorite pilgrimage spot for visitors to Appalachia from across the water. For those unfamiliar, the Carter Family Fold runs Saturday night music and dance events, and we’ve enjoyed many a weekend there, listening to the old-time music and watching the amazing local dancers flat foot – from a woman who often dances with her (willing) dog to an elderly couple tearing up the floor with their moves!

The Carter Family Fold and The Carter Family’s song “The Storms Are on the Ocean” – and the history shared by the Birthplace of Country Music Museum and exhibits like The Appalachian Photographs of Cecil Sharp – illustrate just a few of the many connections between Appalachia and the British Isles. If the subject interests you, start with Child’s book. A world of discovery awaits!

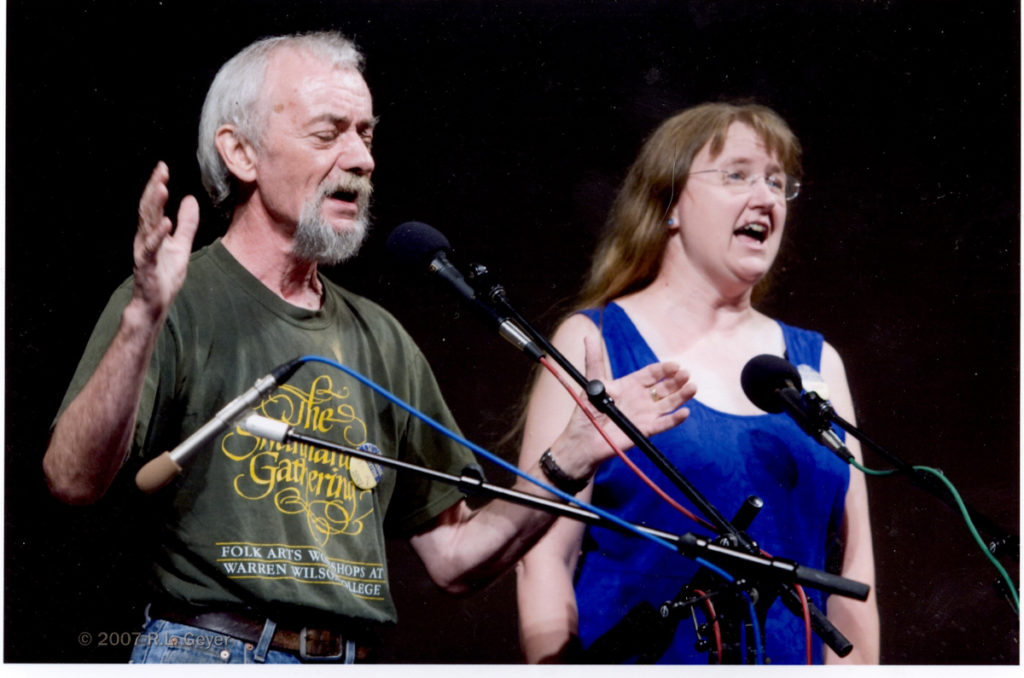

Thank you to our guest bloggers Jack Beck and Wendy Welch, who wrote this blog post touching upon the journey of the “Lord Gregory” ballad, the perfect post to accompany our new special exhibit!

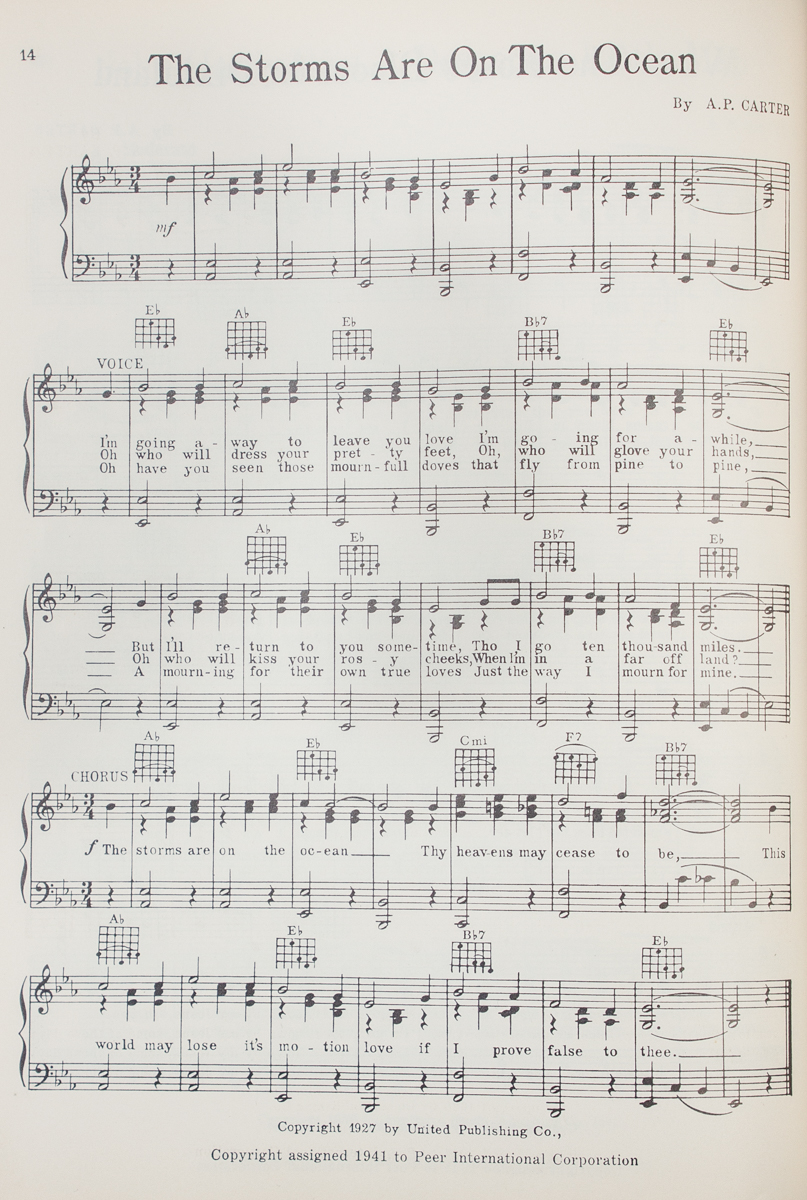

Jack was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, and lived most of his life there. A founding member of Heritage, one of the seminal traditional Scottish bands of the 1970s and 1980s, he was also the musical partner of Barbara Dickson. Awarded an honorary lifetime membership in the Traditional Music and Song Association for his services to Scottish traditional music, he spent five years as external examiner in Scots Traditional song at the Royal Scottish Conservatoire in Glasgow. Jack has lived for the last twelve years in Big Stone Gap, Virginia with his wife Wendy Welch, in the heart of Appalachia and old-time mountain music. Wendy is the author of four books, the most recent Fall or Fly detailing effects of the opioid crisis on foster care. She has a PhD in Folklore, is book editor for the Journal of Appalachian Studies, and was founding director of a storytelling non-profit in Scotland. Together they run a bookstore – Tales of the Lonesome Pine – the subject of Wendy’s memoir The Little Bookstore of Big Stone Gap from St. Martin’s Press.