There’s an old church joke about when Jesus returned to heaven after his time on earth. All the angels gather around to celebrate Jesus’s success overcoming death, and someone asks, “So now what’s the plan? How are we going to tell the world the good news?” Gabriel offers to blow his trumpet. Michael suggests a multitude of heavenly hosts. Jesus looks at the angels and says, “I’ve got it covered. I told these twelve guys, and they’re going to tell some people, and then those people will tell some people…”

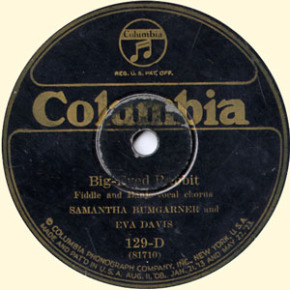

As ridiculous as this sounded to the angels, this method of sharing the gospel tells us something about the music and ministry of Ernest Phipps of Gray, Kentucky, who was born on May 4, 1900. Ernest Phipps and His Holiness Quartet recorded six sides on Tuesday, July 26, the second day of Ralph Peer’s 1927 Bristol Sessions. Their recording of “Don’t You Grieve After Me” was issued with the earliest Bristol Sessions serial number and released in the first batch of Bristol sides in September 1927.

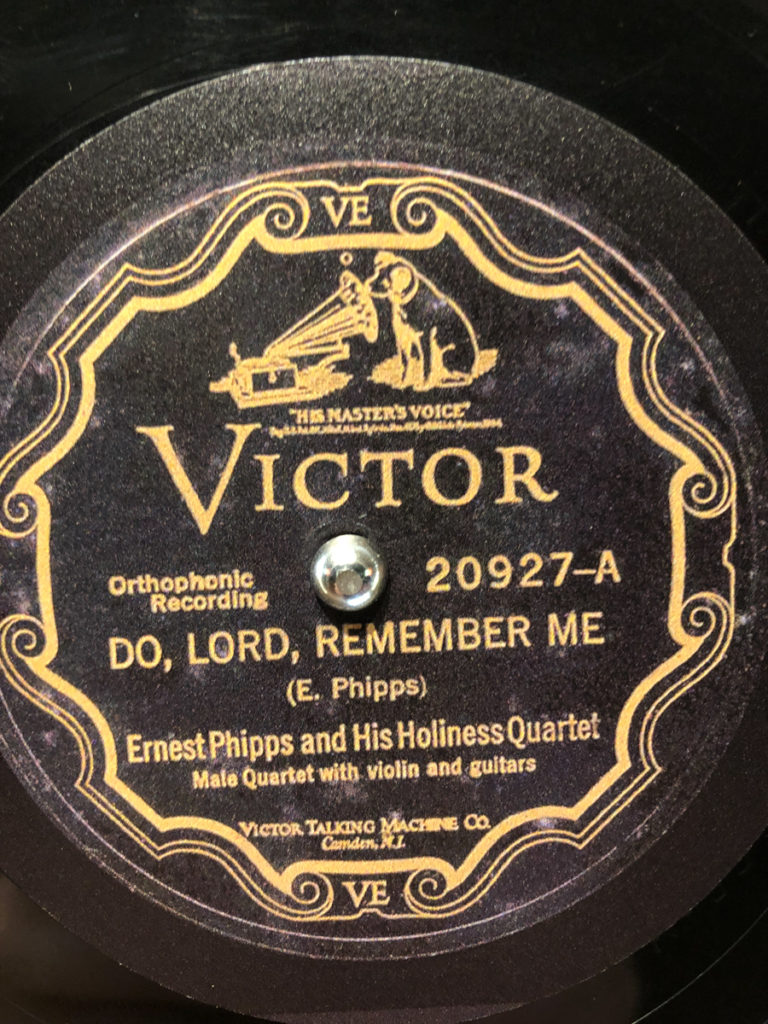

The music Phipps and His Holiness Quartet made in 1927 sounds like spirited old-time music. Phipps sings lead accompanied by a high harmony; a guitar or two and fiddle back the singing, and the fiddle plays the melody on instrumental breaks. Charles Wolfe conjectured that Ancil McVay played guitar and Roland Johnson played fiddle and that perhaps Alfred Karnes, another preacher from the Corbin area who recorded his own gospel sides that week, played the driving guitar bass runs. The singing and playing are raw and real, someone stomps on the one and three, and the distinguishing element of these songs, particularly “Do, Lord, Remember Me” and “Old Ship of Zion,” is a galloping, deep-in-the-beat feel.

Phipps worked his whole life in the coal business, as a miner, a truck driver, and later as co-owner of a small operation. He also preached and sang in the Holiness churches around Corbin, Kentucky from the 1920s until his death in 1963, minus a few years he was in the army during World War II. Much of what we know of his life comes from his youngest sister, Lillian McDaniel, and his stepsons W. R. and J. Randall Mays. Their memories do not fill in the whole picture of Phipps’s life, but they tell us enough to know that his ministry was his major focus, and that his music was likely a component of his ministry. He often visited churches to preach, and would also sing, but no one remembers his visiting churches to sing and not preach.

The idea that Phipps’s recorded music constitutes an early form of mass media evangelism may involve projecting motives from our time onto his, but nothing in Phipps’s story suggests that he sought a career in music; however, much evidence exists that Phipps sought to share his faith. When he returned to Bristol in October 1928, he brought eight members of his congregation – three female vocalists and five instrumentalists – who recorded six songs that “give us some sense of the power and drive of a real Holiness service,” in the words of Charles Wolfe. The group vocals shift moment to moment between harmony and unison singing and overpower the instrumentation on most songs. The string band groove of Phipps’s 1927 sides is replaced here with a less precise but no less energetic backing shuffle. During refrains, a chorus of handclaps on the one, two, three, and four beats propels these songs into a frenetic pace. These sides sound more like field recordings of a church service than commercial records, but Ernest Phipps and Ralph Peer were onto something: “If the Light Has Gone Out of Your Soul” backed with “Bright Tomorrow” sold almost 12,000 copies.

Here’s “Went Up In The Clouds Of Heaven,” one of the songs recorded by Ernest Phipps and His Holiness Singers at the 1928 Bristol Sessions:

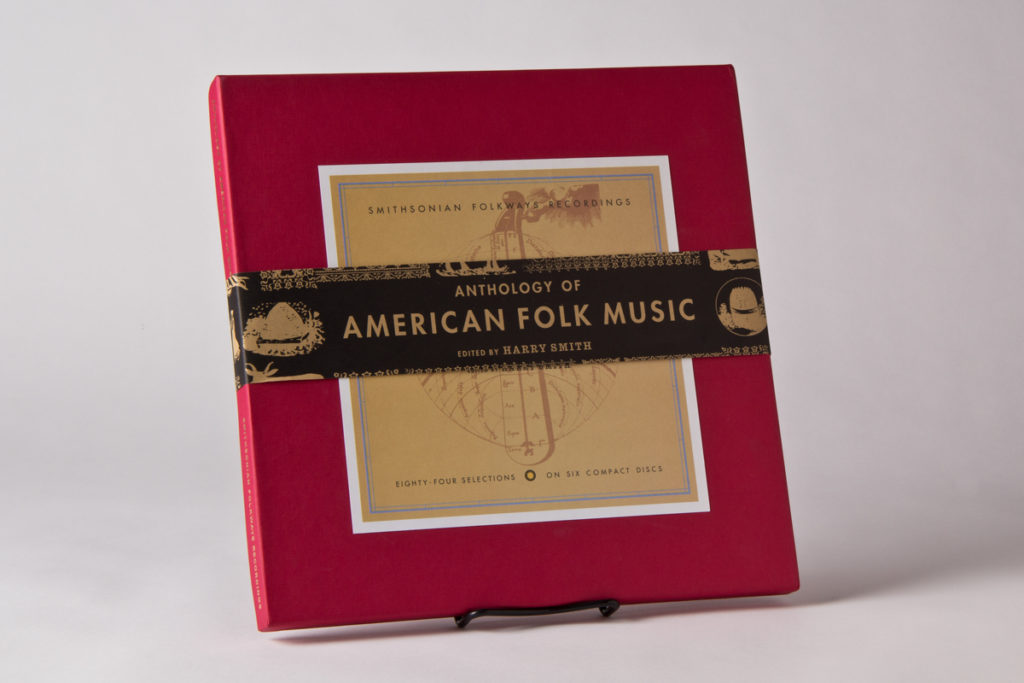

Phipps’s recordings, especially from the 1928 sessions, have sent folk music scholars and fans in a number of interesting directions. Charles Wolfe remarked that Phipps’s recordings preserve “rare examples of the exuberant, ragged, hand-clapping Holiness music” of 1920s Appalachia, particularly Eastern Kentucky. Harry Smith included “Shine on Me” from the 1928 Sessions in his Anthology of American Folk Music alongside the most important American folk musicians of the first half of the 20th century. My work on Phipps suggests that his recordings pioneer a Southern Gospel music antithetical to the harmony singing of the Stamps Quartet, who also recorded at the 1928 Bristol Sessions.

Because of the spirit it preserves and represents, Phipps’s music has lived a remarkable life of its own. The life of Ernest Phipps suggests that his brief recording career served a purpose: to share the gospel with as many people as he could.

Brandon Story teaches English at King University in Bristol, Tennessee. His chapter “Gospel According to Bristol: The Life, Music and Ministry of Ernest Phipps” appears in Charles Wolfe and Ted Olson’s The Bristol Sessions: Writing About the Big Bang of Country Music.