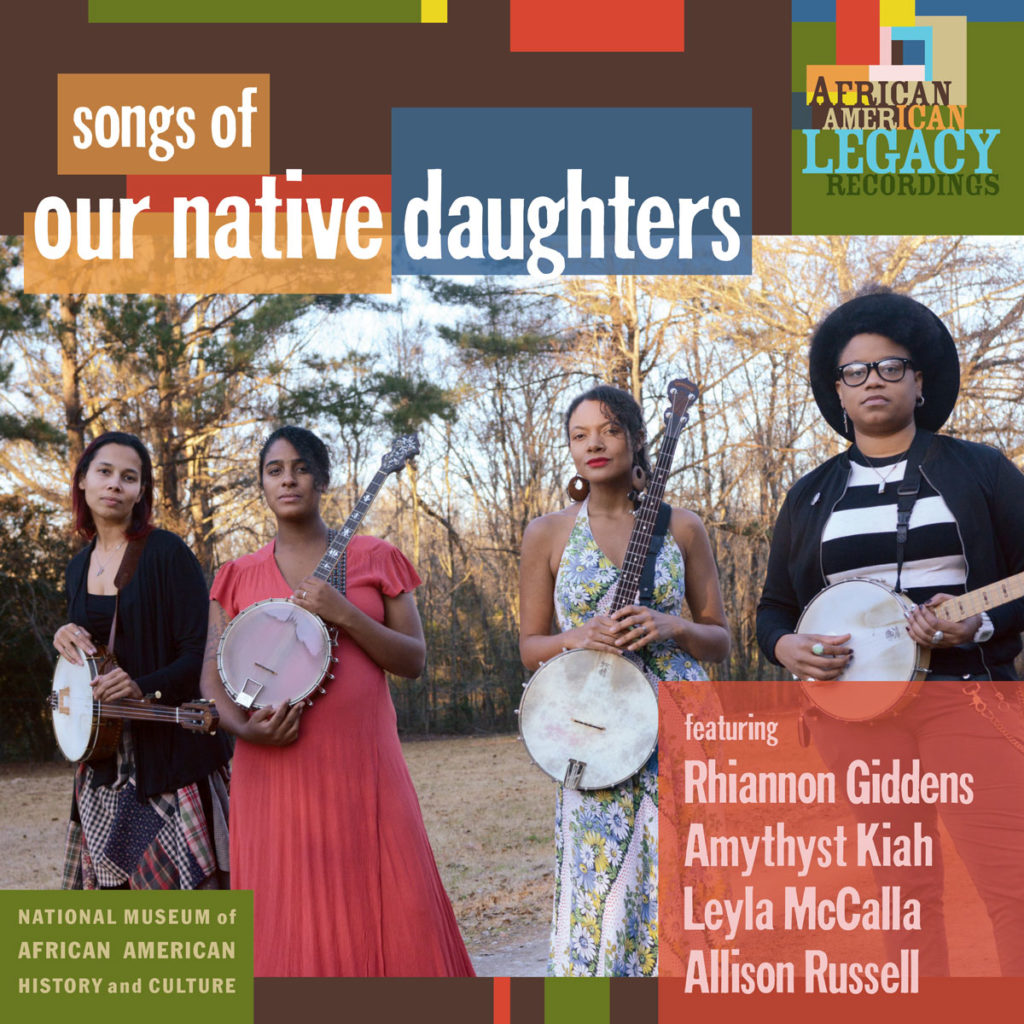

A little over a year ago I was asked by Rhiannon Giddens, co-founding member of the groundbreaking and Grammy-Award winning group The Carolina Chocolate Drops, if I was available to be part of a project with other black female songwriters that focused on the banjo and slave narratives. It is possible that these three concepts had never even been in a sentence together at any time in recent human history.

Rhiannon has been studying slave narratives and the history of the banjo for many years, and her inspiration for the project came from the idea of centering the story of the African diaspora with the voices of black women – voices that have been historically left in the background. Taking a cue from James Baldwin’s Notes of a Native Son, which inspired this project’s namesake, the stories of struggle and resistance come in the form of music. “It is only in his music…that the Negro in America has been able to tell his story. It is a story which otherwise has yet to be told and which no American is prepared to hear.”

Songs of Our Native Daughters aims to contribute to preserving the history of the African diaspora in the Americas through an eclectic mix of folk styles. Rhiannon’s vision for the project centered on the banjo, an instrument descended from the West African lute family, incorporating it into folk music arrangements to tell the stories of ancestors who were brought to the Americas against their will. We today, as descendants, continue to thrive and heal with the power of music despite the adversity that has been endured.

My career was just beginning to blossom when Rhiannon reached out to me about being part of Songs of Our Native Daughters. One year prior she had invited me to open a string of shows for her Freedom Highway album release tour. This new project was certainly an intriguing opportunity, not only from a historical and educational perspective, but also on a deeply personal level.

The album collaborators come from varying backgrounds: Rhiannon and I are both from the American Southeast, Allison Russell is from Montreal, Canada, and Leyla McCalla is a first-generation Haitian-American from New Jersey. We all have our unique perspectives and experiences as black women in North America, and our individual approaches to folk music are very eclectic, bringing so much dynamism to the music on the record.

Rhiannon cast the room well, calling upon Dirk Powell to record and co-produce the record with her at his studio in Breaux Bridge, Louisiana. She also invited Jamie Dick to perform drums and percussion, and Jason Sypher joined on upright and electric bass. Dirk, Jamie, and Jason have been touring and recording with Rhiannon on her previous solo work, so the template for the sound and process was already set.

The nature of four black women playing banjo and writing songs about the stories of our North American ancestors and their struggle was in and of itself a remarkable experience – truly inspiring and healing. There is an emotional and mental aspect to writing such heavy material; I have always been interested in using Southern Gothic style to convey concepts of human nature, and this project by far is the heaviest and most emotionally stirring work I have done. And it has changed me. Today I feel even more convinced in my pursuit of music as one of the best forms of communication, healing, and understanding of each other and our place in the world.

The entire concept of Songs of Our Native Daughters has simply never been done before. Rhiannon is truly one of the most driven and imaginative people I have ever met. To have the courage to dig into some of the subject matter she has tackled and to want to create a medium that relays these stories is simply remarkable. In order to deal with this kind of material – to know the pain and anguish my ancestors went through, to see the shoulders on which I stand, and to appreciate the people that survived and lived to tell their stories – is something that requires much patience and understanding. It was an enormous blessing to be part of this project and to be given the wonderful opportunity to help make these narratives come to life musically.

* Songs of our Native Daughters is released today, February 22, 2019 on Smithsonian Folkways Records as part of their African American Legacy series, which introduces a new way to celebrate black voices during Black History Month. The album is an eclectic folk record, with music styles ranging from minstrelsy, contemporary folk, blues, Appalachian string band, and more. Several publications and media outlets – including NPR, Rolling Stone, The Guardian, and DownBeat – have reached out to Rhiannon, Allison, Leyla, and me about our new project. Check out my website here to learn more about this and other projects I am working on.