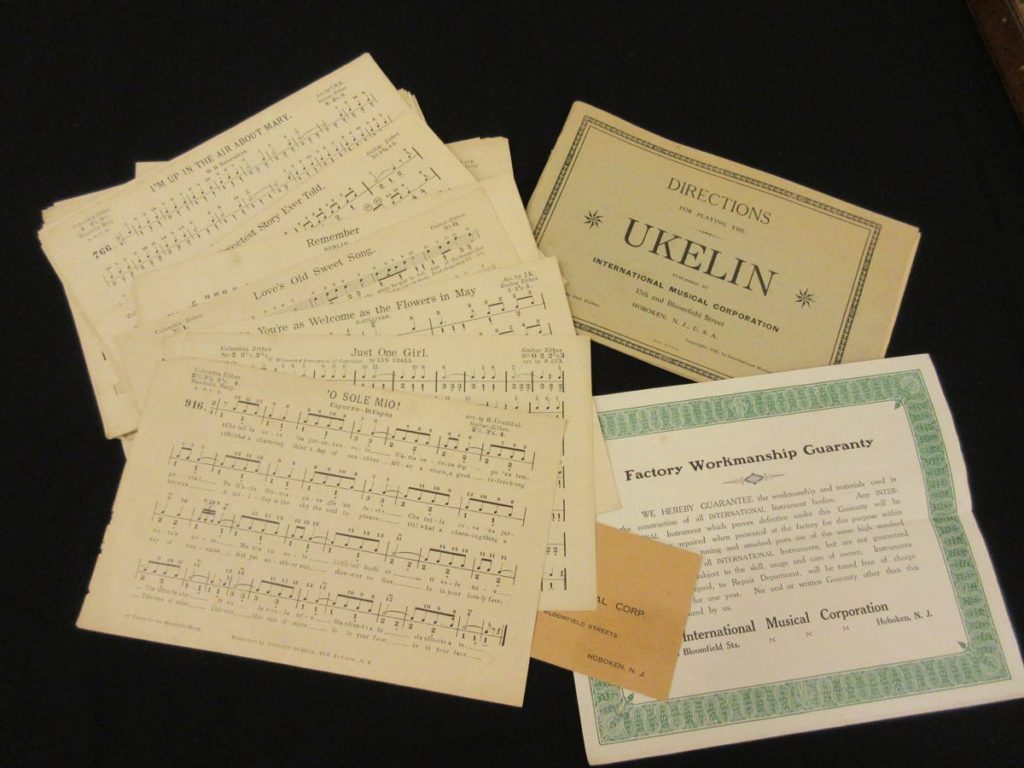

The museum has recently started a monthly community jam, inviting budding and expert musicians alike to come to the museum and make beautiful music together.

So, what exactly is a “jam,” you might ask. A quick search of the internet will return many theories on how the term “jam” originated. My personal favorite is that after a night of shows in the early jazz clubs, members of several bands would gather or be “jammed” together on small bandstands to improvise and play as a group, and thus the jam session was born.

A better definition for jamming would be an event where musicians come together to play and sing music with and for each other. The musicians may or may not know each other and will typically have varying levels of expertise and playing ability. There could be those that just come to listen and observe, but the common goal for a jam is to have fun playing, singing, and listening to music together.

In a jam, it helps musicians to get down to the business of playing music together if they have an idea in advance of what to expect. In other words, having a basic understanding of what is going on in a jam helps facilitate the playing and the flow of the jam. And there is a general jam etiquette that pickers try and follow, giving everybody the best opportunity to participate.

So let me act as your etiquette coach and share the important elements of what you need to know to get the most out of a jam and to be the perfect jammer!

The Three “Musts”

- You must be in tune. Before starting and throughout the jam, use an electronic tuner to keep yourself in tune.

- You must be on the right chord. Do your best to pick up on the chord changes as quickly as possible. It helps to know the common guitar chords by sight even if you don’t play guitar. You can then watch a guitar player who knows the chords and follow him or her.

- You must stay with the beat. Try not to rush, drag, or lose your place in the song.

The Circle

With jams, players arrange themselves in a circle so they can see and hear each other as they play. How large the circle is depends on the preferences of the players. Songs are selected and lead by individual jam members one at a time, going around the circle. The player whose turn it is selects the song and tells everyone the key he or she will sing or play it in. That person is now the leader of the song. Follow the leader!

The Leader

Ok, it’s your turn in the circle. So what do you do? First, you need to tell everyone your song selection and the key it’s going to be played in. And then you must lead this song. This is accomplished by first briefly discussing things like how fast the song will go, who will be kicking off (starting) the song, and any other information that might be helpful to those who may not have heard or played the song before.

Playing Together

Once the leader shares the musical details, the song kicks off – and you are off and picking! A song that is sung will typically start with the kick off and a short instrumental break (solo), followed by a verse and the chorus, and then repeated with break, verse, chorus, break, verse, chorus with different instruments providing the breaks each time.

Body language and eye contact play a very important role in deciding who will play a break in a song. While the song is being sung, the leader is looking around the circle in search of those who would like to take a break (solo). Pickers that feel comfortable playing a break will also be making eye contact with the leader. After a verse and chorus have been sung, the leader will nod toward the picker he or she has chosen for the break to take the floor – the melody and chords of the verse are typically played during this solo interlude.

After the break is played, the singer will sing another verse and chorus, and another picker will be chosen for the next break. These steps are repeated until all verses are sung and everyone who wants to has had a chance to take a break. Pickers that are not comfortable playing breaks simply avoid eye contact with the leader – so keep your eyes down until you’re ready! (It makes me think of what happens at an auction – where it’s best to sit on your hands so that you don’t accidentally buy something…) However, if you make eye contact by accident and the leader should give you the nod and you don’t want the break, a simple shake of the head signals to the leader that you want to pass. After the final break has been played, another chorus is sung signaling the end of the song.

Instrumental songs are led much the same way, minus the singing, of course. After everyone has had a chance to take their break, the picker that started the song with the kick off will play the last break and signal the end of the song, typically with an outstretched leg into the circle.

Give It a Try!

The museum’s community jam is open to everyone of all talent levels. I can’t think of a better setting to sharpen your playing skills than a local jam. For the beginner, lessons are where you start but once you have mastered the chords of your instrument, the real fun begins when you get out and begin playing with others!

So mark your calendar for the third Saturday of each month from 2:00 to 5:00pm, and come join us at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum for our community jam — the next one is on Saturday, July 21. The museum is a great space for us to come together and pick, to learn from one another, and to have fun – all you need is your instrument and the courage to jump straight in. And remember listeners are also invited to attend. Come and enjoy!