By Ed Hagen, Gallery Assistant and Guest Blogger

What’s the difference between Country and Western?

Many people are familiar with a popular scene in The Blues Brothers movie where the character played by Dan Ackroyd asks the woman tending bar, “what kind of music do you usually have here?” She responds, “Oh, we got both kinds, country and western.” Although intended as a joke, the question can be taken seriously. They are two distinct musical styles. And both styles were popularized by musicians from the 1927 Bristol sessions.

The words we use to describe music have changed almost as much as the music itself. In the 1920s, the music we now refer to as country was known as hillbilly music. The phrase “country and western” first started to appear in print in 1944, with peak usage in 1973. Billboard charts, which initially had listings for “folk” and “hillbilly” records, switched to “country and western” in 1949, and used that label before settling on “Hot Country Singles” in 1962. Listeners in the 1950s knew what you meant when you said “country and western.” Today, not so much.

Country music has its roots in Appalachian music, which in turn can be traced to Scotch and Irish folk music and African musical traditions. It typically involves storytelling. Popularized by the Carter family, it is the music associated with Nashville and the Grand Ole Opry. The emphasis in country music is on melody and lyrics. Think of songs like He’ll Have to Go, I Can’t Stop Loving You, He Stopped Loving Her Today, and Jolene. These songs are country, not western.

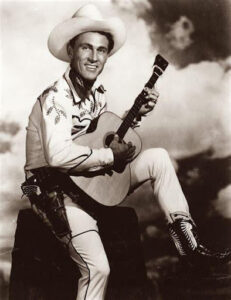

It is a bit harder to define western music. Many listeners would think of cowboy songs sung by artists like Gene Autry and the Sons of the Pioneers. Autry started out as an obscure radio singer in Chicago. His big break came in 1935 when he was signed by Republic Pictures to make low budget Westerns. These films featured Autry using his own name, breaking into a song from time to time, often while riding his horse Champion. His theme song was Back in the Saddle Again, but he is also remembered for his popular Christmas songs: Santa Claus Is Comin’ to Town, Here Comes Santa Claus, Frosty the Snowman, and Rudolph, the Red-Nosed Reindeer.

The Sons of the Pioneers was a vocal group formed in 1933 in the Los Angeles (LA) area. The original trio consisted of Bob Nolan and Tim Spencer and was led by a truck driver and fruit picker named Leonard Slye. They soon added the brothers Karl and Hugh Farr. These five are often referred to as the “Original” Sons of Pioneers since the band has continued to rotate members and is still active today! LA in the 1930s was a good place to be for talented cowboy singers. The group found work in western movies and recorded a best-selling record, Tumbling Tumbleweeds. In 1937, Slye left the group, changed his name to Roy Rogers, and became one of America’s favorite singing cowboy stars. His place in the Sons of the Pioneers was taken by Ken Curtis, who is better known today for his role as Festus in the TV show Gunsmoke.

These cowboy songs were typically accompanied by simple first-position triads played on a guitar. In fact, first-position triads are often called “cowboy chords” today.

But that’s just one type of western music. Another variant can be traced to the Bristol sessions, specifically to up-tempo tunes recorded by Jimmie Rodgers. Rodgers, a native of Mississippi, was strongly influenced by African American acoustic blues players that he met and played with when he worked on railroads in the South and West. Rodgers often played songs that featured bass runs between the chords that swing hard.

In the 1930s and 40s the big jazz bands of stars like Benny Goodman and Count Basie dominated popular music, and a number of them started specializing in western songs. The most famous of these western swing bands were organized by Bob Wills (the Texas Playboys) and Spade Cooley. Western swing bands featured fiddles, horns, brass, and piano players. Playing in giant ballrooms like the Aragon in Santa Monica, they got the volume they needed with drums and modern electric and steel guitars, instruments that drowned out conventional acoustic basses. So guitar players like the Texas Playboys’ Eldon Shamblin, playing in the Jimmie Rodgers style, mixed bass runs with the rhythm chords. This style worked for Rodgers and Shamblin because they both swung those bass lines hard.

Western swing, unlike cowboy songs, was dance music. It differed from big band swing because wasn’t based on jazz music. Take, for example, a song like Take Me Back to Tulsa, which was originally a traditional fiddle tune, Walkin’ Georgia Rose. The Texas Playboys changed the words and had a hit with it as a big band tune. The underlying harmony of the song was just two cowboy chords. Western swing bands didn’t play complex extended chords or rhythm changes. But they got you out of your chair.

The big western swing bands died out at about the same time that the popular jazz swing big bands broke up, probably due to the economics of keeping a large band together. But western music stayed popular with the next generation of smaller combos led by western stars such as Ernest Tubb, Buck Owens, and Merle Haggard. Powered by drums and electric instruments, these more modern western stars kept people dancing.

So when the bartender told the Blues Brothers they have both kinds of music, perhaps she meant the bar featured old-time and traditional country musicians as well as western and western swing acts! Either way Jake and Elwood probably were not what the crowd at Bob’s Country Bunker was expecting.

![The cover of the original "Sacred Harp" hymn book. It is old and worn, reading "The Sacred Harp, a Collection of Psalm and Hymn Tunes, Odes, and Anthems; selected from the most eminent authors, together with nearly one hundred pieces never before published. Suited to most metres, and well adapted to Churches of every denomination, singing schools, and Private [word obscured]. With Plain Rules for Learners. By B.F. White and E.J. King](https://american-today.info/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/image11-300x199.jpg)