What I wouldn’t give to have met Lesley Riddle.

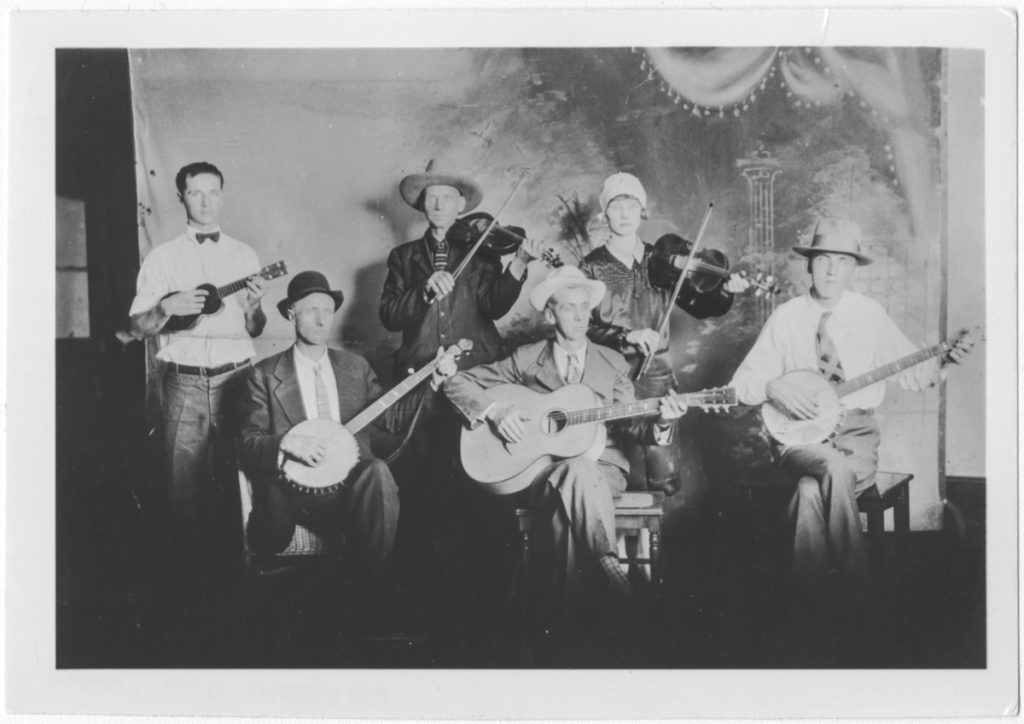

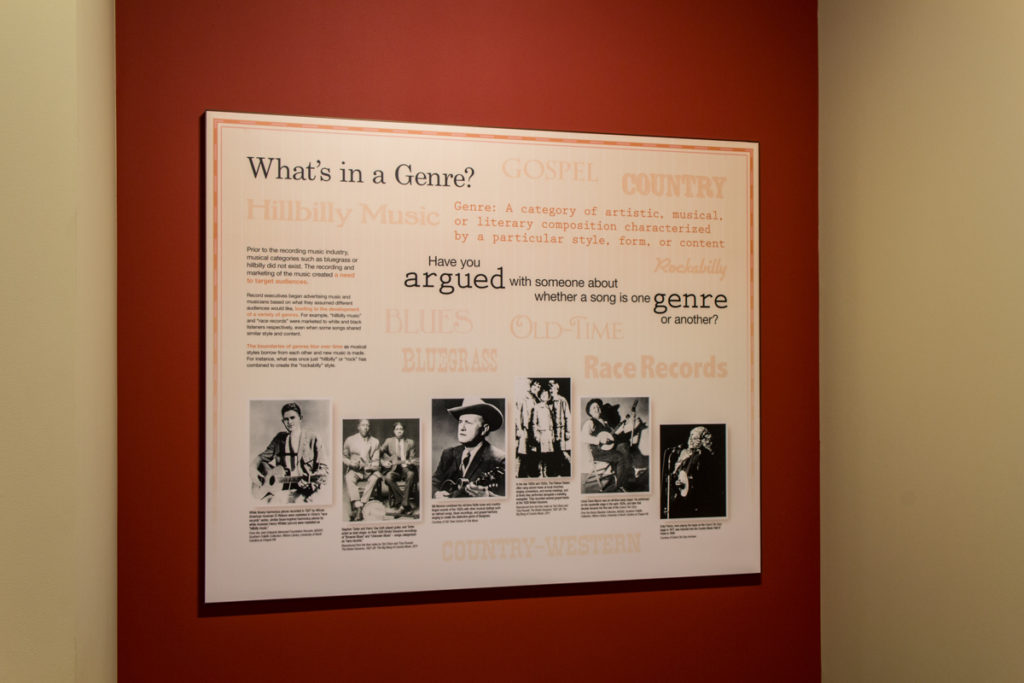

Credited as having influenced one of the world’s most prominent families in country music history, Lesley Riddle’s legendary interactions with The Carter Family offer a glance at the messy realities of musicians making a living in the 1920s and 1930s. This history shows that black and white musicians came together in ways that made the music richer, more complicated in its honest reflection that defied the genre catalogs of the industry.

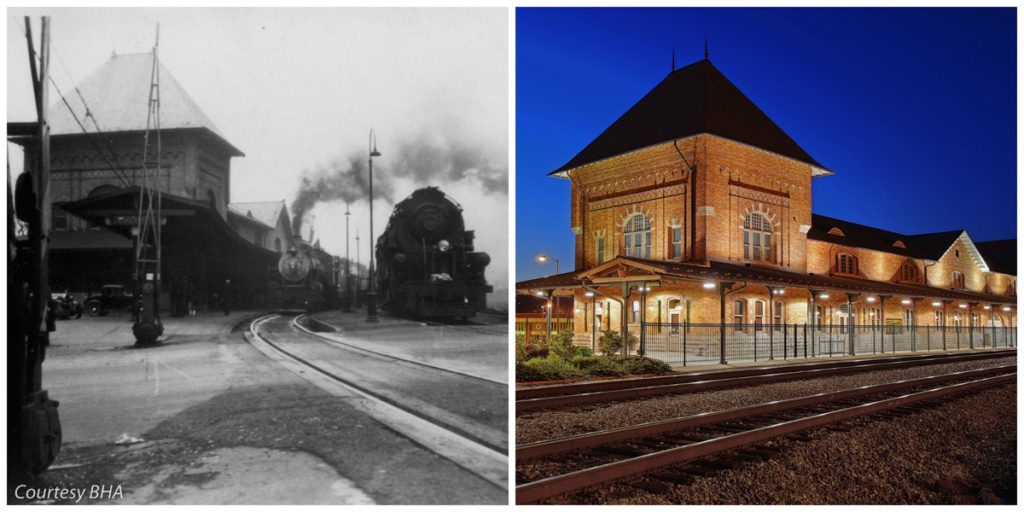

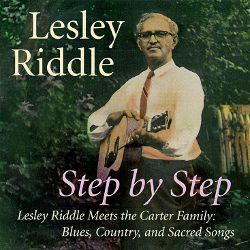

A. P. Carter met Lesley Riddle in the late 1920s in Kingsport, Tennessee. This meeting was the beginning of a musical interaction that would impact The Carter Family’s music, as Riddle traveled with Carter to collect songs throughout the region and helped shape Maybelle’s guitar techniques. Sadly, Riddle never made his living in music himself; however, it is his contribution to country music for which he is most remembered.

From this history, I also wish I could have met Lesley Riddle and A. P. Carter together. Riddle having lost a leg in an accident and Carter with a constant tremor, the two men stand as an odd couple in the canon of country music history, almost a tragic comedic duo looking a segregated South (and a segregated music industry) straight in the face as they traveled the hills of northeast Tennessee and southwest Virginia to hear and learn the songs that were being sung. At a minimum, it’s inspirational that the two rambled forth together; however, if their partnership was a non-issue in the hollers where they traveled, it invites even more consideration.

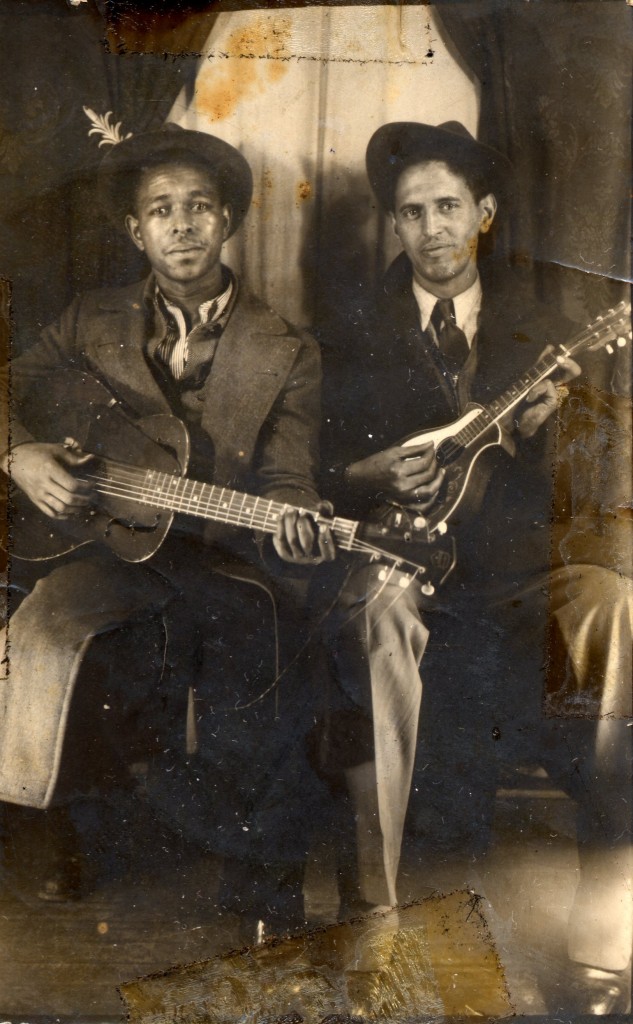

Born on June 13, 1905 in Burnsville, North Carolina, Riddle spent much of his childhood with his paternal grandparents near Kingsport, Tennessee. After a cement factory accident robbed him of his right leg, Riddle took an interest in the guitar and mandolin. The Traditional Voices Group of Burnsville, North Carolina’s Mountain Heritage Center has compiled a full bio of Riddle if you want to read more about his life.

Riddle met other musicians during his time in Tennessee, and he was soon a regular in the area’s music scene, especially with other black artists including Steven Tarter, Brownie McGhee, and John Henry Lyons. It was Lyons who introduced Riddle to Carter, and he soon became fast friends with the family, staying with them at their home in Maces Springs, Virginia, for weeks at a time and accompanying Carter on his song collecting trips.

Maybelle Carter credited Riddle with teaching her the “bottleneck” style of guitar picking, in which the index finger plays the melody while the thumb keeps the rhythm on the bass strings. Of Maybelle’s playing, Riddle said: “You don’t have to give Maybelle any lessons. You let her see you playing something, she’ll get it – you better believe it.” Riddle taught The Carter Family such songs as “The Cannon Ball,” “I Know What It Means to Be Lonesome,” “Coal Miner Blues,” and “Let the Church Roll On.” In 1942, Riddle and his wife moved to Rochester, New York, and lost touch with both The Carter Family and music. A few years later he sold his guitar.

In the mid-1960s, Mike Seeger met Riddle, and he interviewed and recorded him on several occasions during the 1960s and 1970s. With Seeger’s influence, Riddle performed at such venues as the Smithsonian Folk Festival and the Mariposa Folk Festival, as well as the Carter Family Fold before he passed away in 1980.

Some of Seeger’s interviews capture the organic nature of the encounter between A. P. Carter and Lesley Riddle. “I played a couple of songs for him [A. P.] and he wanted me to go back home with him right then and there,” said Riddle in one interview. “I went over to Maces Springs with him and stayed about a week. We got to be good friends and for the next three or four years I continued going over to his house, going where he wanted to go. I went out about 15 times to collect songs.” Riddle continued: “He was just going to get old music, old songs, what had never been sung in sixty years… He was going to get it, put a tune to it, and record it.” Lucky for us, the materials related to Riddle are available to researchers as part of the Mike Seeger Collection at the Southern Folklife Collection at UNC-Chapel Hill – the collection houses a whopping 70,000+ items in total!

Riddle’s participation was a vital part of Carter’s work to collect traditional songs for the record producers he was working with. “If I could hear you sing, I could sing it too,” said Riddle. “I was his tape recorder. He’d take me with him and he’s get someone to sing the whole song. Then I’d get it and learn it to Sara and Maybelle.”

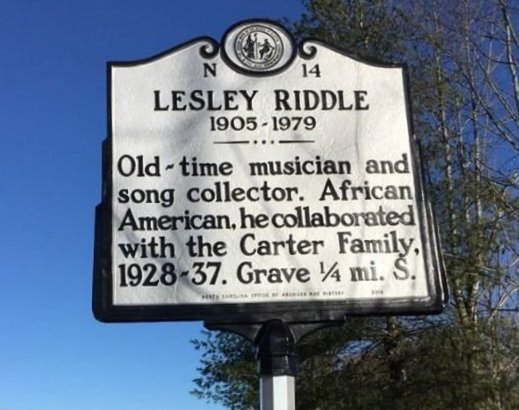

So while we might not get the chance to meet Lesley Riddle now, his legacy lives on, and if you’re around Burnsville you may meet him in some fashion. Last year a North Carolina Highway Historical Marker was placed to honor Riddle’s work in country music along Burnsville’s Highway 19. And on June 30 of this year, Traditional Voices will present the annual Riddlefest in honor of the music of Lesley Riddle. Riddlefest 2017, featuring David Holt and Josh Goforth with guest Roy Andrade joining Holt for a special seminar, will be the 10th anniversary of this annual concert event.

Jessica Turner is the Director of the Birthplace of Country Music Museum.