By Sam Parker, AV & Technology Specialist at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum.

This month marks the 148th anniversary of Thomas Edison’s cylinder phonograph, which was assembled on August 12th, 1877. But did you know, the history of sound recording technology doesn’t start with Edison, but rather was the culmination of decades of research and innovation? The anniversary of Edison’s phonograph inspired us to take a look at a French inventor whose device, although not commercially successful, is a landmark in the history of recorded sound that pre-dates the phonograph.

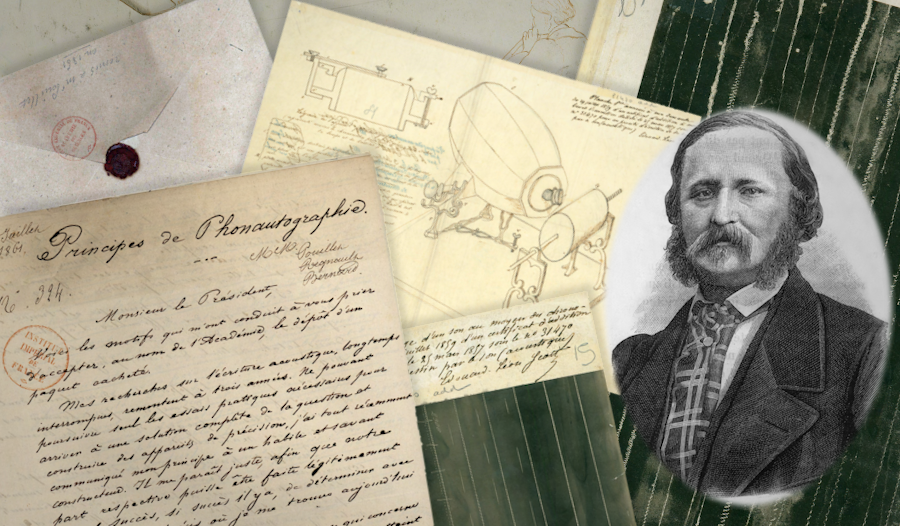

The earliest known song recorded by a man-made device was sung while Edison was still a newsboy, but who was responsible for this momentous accomplishment? Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville worked as an editor at a publishing company specializing in texts about scientific research and news in Paris. While reading about scientific innovations, he was inspired to replicate what the camera did, but for words instead of images.

Similar to Edison, Scott’s work built on the innovations and technologies of his predecessors and contemporaries. In a letter to the President of the French Academy of Sciences, he wrote about some of his predecessors:

As precedents, I had before me the siren of Cagniard-Latour, the toothed wheel of Savart, both suitable for counting the vibrations of the sounding body; Wertheim’s process for writing the vibrations of a tuning fork; the electromagnetic tour described by Mr. Pouillet for the same object. I have taken a step further: I write not only the vibrations of the bodies that primitively vibrate, but those transmitted mediately by a fluid — that is, by the surrounding air.

This letter was more than just a description of his idea; it was part of a process in 19th-century French academia to establish primacy when credit is given for an invention. At the time, when an inventor had an idea for a new innovation, they write it down, place it in a sealed envelope, and deposit it at the Academy’s office in Paris. These letters are not intended to be read– at least not immediately. The letters can only be opened by the person who left them, or their family, after the inventor’s death. This system was created so that, in a situation where two different people claim to have made the same invention, the one who invented it first can prove it with a dated letter verifying when they developed the concept. This came into play a decade later when Edison began working on his phonograph. Once it began to attract attention in the papers, a Parisian inventor requested the Academy open his letter, in which he wrote about a process of replicating sound very similar to Edison’s nearly two weeks before Edison did.

After combining the technologies and discoveries of his predecessors, Scott and a “skillful and learned manufacturer” built what was essentially a large mechanical version of a human ear. They called it the phonautograph. The phonautograph used an acoustic horn (similar to Edison’s phonograph) attached to a diaphragm to vibrate a boar’s bristle, inscribing the vibrations on a plate of glass covered with a thin layer of lampblack. For the first time, a physical record of sound waves had been captured.

So then, why do we celebrate the phonograph and not the phonautograph?

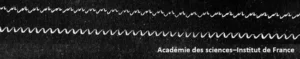

There is one key factor that kept the phonautograph classified as a scientific curiosity instead of a culturally revolutionary invention. Sure, the phonautograph created recordings, called phonautograms, but Scott had not yet devised a way to play them back. Scott’s recordings looked, to the untrained eye, like scribbles on a plate of dark glass or piece of paper. Scott hoped that he would be able to develop a method to read the sound waves, but this never came to fruition. Despite not being able to read sound, Scott was aware that his new technology was groundbreaking. He once remarked, “I see the book of nature opened before the gaze of all men, and, however small I may be, I dare hope to be permitted to read it.”

Scott worked with the French Société d’Encouragement pour l’industrie Nationale (Society for the Encouragement of National Industry) and German Physicist Rudolph Koenig to further develop the phonautograph, moving from a small plate of glass to a cylinder that could capture around 20 seconds of sound. They marketed the phonautograph as a research tool for further understanding acoustics and the nature of sound waves, and recorded numerous phonautograms to examine the represented changes in pitch, tone, and timbre in speech and song.

For a long time, we were unable to recover the sound from phonautograms, but in 2008, researchers with FirstSounds developed a way to reproduce the recorded audio. For the first time in over a century and a half, we can listen to the first ever song recorded by mankind: a French folk tune, “Au Clair de la Lune,” sung by Scott himself. The biggest challenge was that the phonautograms were not recorded with the intention of being played back. They contained smudges and skips, and the speed of the recording often changed depending on how fast the phonautograph’s crank was being turned, which led to wildly varying pitches. FirstSounds was able to overcome these challenges using modern technology similar to the process recently used to recover our own transcription disc.