By Sam Parker, AV & Technology Specialist at the Birthplace of Country Music Museum.

From the campfires of Valley Forge, to religious reformers in the First Great Awakening, to even our journey into space, LGBTQ+ people have been present and participating throughout American history. The American music industry, and even country music, are not exempt from their influence. While strict social norms and regular violence forced many early queer musicians to hide their identities, some decided to take a stand regardless of the consequences. To celebrate Pride Month, let’s explore the life and work of country music’s first openly gay musician, Patrick Haggerty.

Patrick Haggerty was one of ten children born on a Washington dairy farm in 1944. His father, whom Patrick would later refer to as the “Saint of Dry Creek,” understood that his son was different. Not many farmer’s sons in the 50s were asking their fathers to help them make wigs out of baling twine for a drag performance at a talent show. It was also not very common for farmers to give their sons tips on how to do better at the next one on the drive home. In his youth, Patrick won a 4-H cooking contest and was invited to Canada to demonstrate his skills for Queen Elizabeth II. When his father saw Patrick practicing his curtsies in a cooking apron, he wasn’t bothered by his son behaving like a proper lady, what bothered him was that his son was curtsying to the Queen of England! The Haggertys were Irish, after all. Patrick’s father didn’t want his son to be ashamed or hide himself as he later recalled his father telling him, “Over and over again in a hundred different ways … not to sneak; he said it would ruin my immortal soul.”

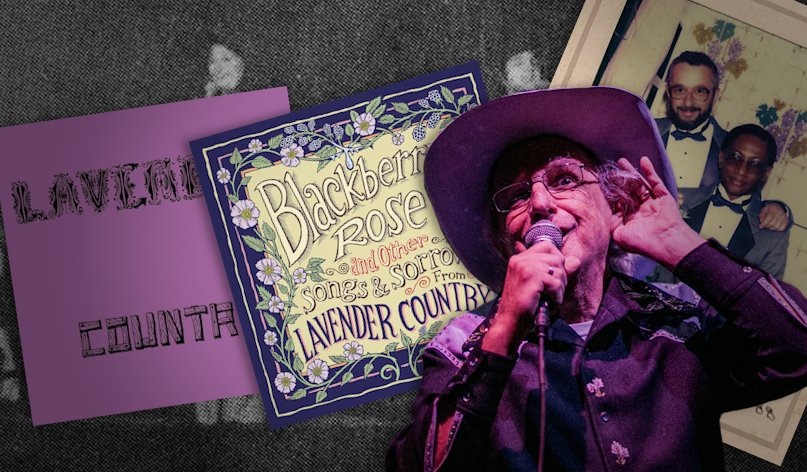

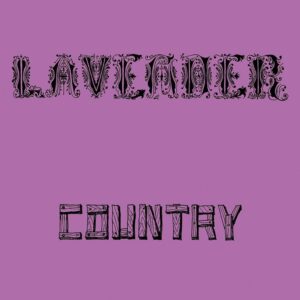

Patrick took his father’s words to heart and credits the moral as his inspiration for creating the first gay country music album in the early 1970s, Lavender Country. In the years following the Stonewall Uprising, the American LGBTQ community was energized, producing numerous works of art and protest collectively. Patrick’s band, also called Lavender Country, was one of these efforts, combining Patrick’s singing with Michael Carr on keyboard, Robert Hammerstrom on guitar, and Eve Morris singing and playing fiddle. Seattle’s LGBTQ community entirely funded their self-titled first album– the studio, promotion, and distribution of the album’s 1,000 copies was all a community effort to get their message out in the open. This decision was made to avoid those in the country music industry who would have refused to produce their music, or demanded significant changes to it. Patrick believed that Lavender Country would be his first and last album due to its controversy– “I knew Lavender Country would define me musically, and I couldn’t have a career anywhere in music because I wrote it. … But I knew that when I made it and I’ve never regretted that decision.”

Notably, Lavender Country’s music was written to speak directly to its queer audience, especially those living closeted lives in rural areas, those who did not understand their feelings, what they meant, or what to do about them. The songs addressed the intersectionality of gay liberation, the necessity of anonymity in gay relationships at the time, and the prospect of a future where people can live and love as they please.

Yet, Patrick treats the question of “is it real country?” with derision. “If you challenge my credentials on my country-ness,” he said in an interview, “do so at your own peril.” Along with the rest of Lavender Country, Patrick performed at the first Seattle Gay Pride celebration in 1974, along with numerous other Pride events in the Pacific Northwest over the next two years. Shortly after the album’s release, a DJ for a Seattle radio station was fired for playing one of their songs, which featured an explicit title and lyrics in line with their campy, proud, and out theme.

The band broke up in 1976, and Patrick began to focus on working as an activist for anti-racism and pro-LGBTQ causes. He ran unsuccessfully for Seattle City Council, as well as the Washington House of Representatives. He co-parented two children and eventually met his future husband, Navy veteran J.B. Broughton, with whom he continued his activism as the AIDS crisis set upon the American queer community.

Patrick continued performing here and there, mostly at retirement homes for older audiences, and a couple publications made some mention of Lavender Country as the first openly gay country group. Still, Patrick’s comeback wouldn’t really come until someone uploaded one of his album’s songs to YouTube in 2014, leading to renewed interest in Lavender Country. Their original 1973 album was re-released under the Paradise of Bachelors label, and Patrick’s music experienced an explosion of popularity. Patrick toured across the country, gave interviews on the radio, appeared in documentaries about himself, and the album Lavender Country was even adapted into a modern ballet performance. In 2019, after 46 years, Lavender Country released their second full-length album, Blackberry Rose and Other Songs and Sorrow. Patrick died of complications following a stroke on Halloween of 2022, though his legacy as an activist and musician lingers. When asked how he feels about his music’s comeback during Lavender Country’s 2014 revival, he said, “…before I go to my grave, I’m getting the last laugh, because Lavender Country is going to outlive me.”